The term “heart surgery” carries with it a certain amount of baggage. Many are familiar with the grisly imagery of a patient being “cracked open,” receiving what’s known as a

sternotomy, so the surgeon can have full access to the patient’s heart. Even looking past those gnarly optics (not every heart surgery requires a sternotomy, after all), the very concept of surgery on the heart is an inherently scary, intrusive thing.

Here’s the rub: Lots of us are going to need heart surgery one day. And while there are myriad heart surgeries and procedures to choose from, one in particular has seen significant developmental surges in the past several years and is proving to be a promising option for younger patients: According to a 2015 report from the American Heart Association scientific sessions, somewhere around 100,000 Americans undergo aortic valve replacement (AVR) annually — and that’s a number on the rise.

Thankfully, recent developments to both the technology and technique have resulted in a field rapidly evolving to improve the safety and comfort of a procedure that had, until recently, been hugely invasive.

Along Comes TAVR …

Much of the excitement surrounding AVRs as of late pertains to a procedure known as transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Howard C. Herrmann, MD, director of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratories at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP), explained the procedure:

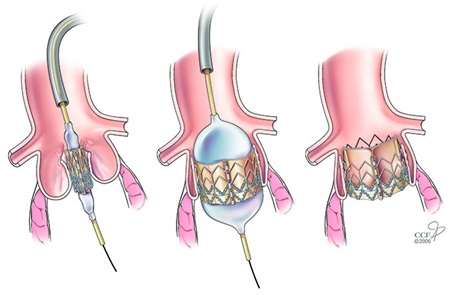

A TAVR diagram. Image: heart-advisor.com

“A valve sewn inside a stent is crimped on a balloon, threaded up through an artery in the leg, and implanted inside the dysfunctional valve of the patient,” he said. “We don’t cut out the old one; we put this one

inside the old one. For this reason, many call it a transcatheter aortic valve implantation rather than a replacement.”

Replacing a dysfunctional aortic valve through a catheter means circumventing the open surgical approach, which means no large incisions, no sternotomy, no need to stop the heart by placing the patient on cardiopulmonary bypass, and a dramatically improved recovery time. It’s something so markedly different from traditional heart surgery that Herrmann doesn’t even like to refer to it as “minimally invasive,” as that carries with it the implication that TAVR is surgical in nature.

Introduced in France in the early 2000s, the first TAVR here at Penn was performed at HUP in late 2007 by Herrmann and Joseph E. Bavaria, MD, vice-chief of Cardiac Surgery. Since then, development and use of TAVR has exploded nationwide. According to Herrmann, between HUP and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center (PPMC), Penn Medicine does about 450 TAVR procedures per year — a number that surpasses the surgical AVRs performed annually.

The increase in utilization is both driving and being driven by the continued evolution of the procedure itself, Herrmann noted.

“We’re now in the third generation of these devices,” he said. “They’re getting smaller, functioning better, and becoming easier to implant. We’ve learned a lot over the past 10 years.”

A standard TAVR procedure, Herrmann said, now often takes less than an hour. Patients who undergo it are kept awake, in a form of conscious sedation called moderate monitored anesthesia care — meaning they don’t have to go under general anesthesia, and they avoid having to go on a ventilator.

“It’s not really the future, it’s the present. It’s here. At Penn, it’s the majority procedure for patients with aortic stenosis. If it proves to be as good as surgery in low-risk patients, it will progress even more rapidly than it already has.”

— Herrmann, on TAVR

It also means recovery is significantly hastened, with most patients going home two days after the procedure. Compared to open heart surgery — which requires not only general anesthesia but being placed on heart-lung bypass and carries with it a months-long recovery process — it seems to be night and day. Avoiding the rigors of surgery was the motivation behind initially performing TAVR on only the patients who were most at risk of suffering serious complications in an open surgical setting. As results have come in and data has been collected, the field has moved toward moderate- and even low-risk patients.

For some of those patients, it isn’t quite moving fast enough:

“Patients definitely prefer TAVR to open heart surgery,” Herrmann said. “They’re driving these studies and the indications quite a bit. When we see an older patient who appears to be relatively low risk for open heart surgery and therefore isn’t really eligible for TAVR, they’re not happy about it. They want TAVR.”

… but Let’s Not Hang Up Our Scalpels Just Yet

But while the potential advantages of TAVR are readily apparent, there are a number of factors standing in the way of its replacing surgical AVR entirely.

First and foremost is the problem we always have with new medical advancements: TAVR simply isn’t yet old enough for us to have long-term data.

“What we don’t know yet are the absolute, long-term results,” Herrmann said. “We don’t have the 15-year follow-up that surgery has, because we’ve only been using the current generation of valves since 2015.”

Data on the earlier generations of valves are available to around the 5- to 8-year mark, but beyond that we just have to wait and keep monitoring — which is, in part, what’s keeping TAVR from being the go-to procedure for everyone.

However, even those patients who don’t qualify for TAVR and have to undergo open surgery today will experience something far different from those patients who underwent open surgery only 10 or 15 years ago.

“On the surgical side, there are some innovations in technology that have been exciting, and we’ve been fortunate to be a part of research at Penn,” said Wilson Y. Szeto, MD, chief of Cardiovascular Surgery at PPMC. “There are new rapid deployment valve platforms that surgeons can implant more quickly, to minimize operative time.”

According to Szeto, in addition to helping pave the way with TAVR, Penn Medicine has been involved with the development of minimally invasive approaches to open surgery for AVR. While he noted there is still some debate over the advantages of smaller incisions such as a partial sternotomy (in which only three to four inches of the sternum is incised, rather than the entire sternum), most physicians generally acknowledge that the minimally invasive approach improves patient satisfaction, and likely is associated with less pain and quicker functional recovery.

While the rapid deployment valves Szeto mentioned definitely improve implantability — which is to say, they allow for shorter implant time when compared to traditional suture-based valves — he added there exists a lack of long-term durability and performance data similar to the one with TAVR.

That said, lack of data is simply that: A lack of data. It isn’t an implication that the newer valves will perform poorly in the long run, and in the meantime, the technology is constantly moving forward.

“There’s always this constant innovation and refinement of the current platforms,” Szeto said. “There are always new valves coming out on the market.”

This all should be of particular interest to younger patients, who have a somewhat difficult choice to make: Biologic valves tend to last only about 12 to 15 years in younger patients, which means a 40-year-old who receives a tissue valve today will likely need multiple replacements over the rest of his or her life. Alternatively, they could choose to go with a mechanical valve — which could potentially be a permanent fix, but would also require the patient to be on blood thinners for the rest of his or her life.

And therein lies where the rapid development of TAVR can become a factor even for younger, lower-risk, non-qualifying patients: Choosing a biologic valve may mean open surgery today, but it doesn’t necessarily mean open surgery in a decade or so.

“In 10 to 15 years, the valve being implanted and the surgery being done could be very different,” Szeto said. “The next rescue operation for a failed bioprosthesis could be a transcatheter valve-in-valve. This is already the case in older, higher risk patients, and is currently being performed routinely. You could have open, minimally invasive surgery today, and in 12 to 15 years when the valve fails, we may be putting in a transcatheter valve. We’re expanding to younger, lower-risk patients. That’s exciting.”

For many patients on the cusp of needing AVR and wanting to avoid serious surgery, it can be a bit of a waiting game. You can’t rush long-term data. Still, the combination of TAVR’s indications moving steadily toward lower- and lower-risk patients — and the improving technology and techniques driving surgical AVR — means the options for a patient in need of AVR are more attractive than ever before.