“It’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, but perhaps there is a key.” The famous trope originated in 1939 in a statement from Sir Winston Churchill on the role the Soviet Union might play in World War II. But it’s also a pretty accurate description of one of the most pervasive, costly, and deadly medical problems in the world.

Nearly 15 million babies in the world are born prematurely every year, and recent data show the number is on the rise. Preterm birth costs nearly $26 billion annually, and puts babies at an increased risk of death and serious illnesses such as cerebral palsy, cognitive impairments, or sensory conditions. Advanced care for premature infants has led to increasing survival rates for the tiny and fragile patients, but the exact cause of premature birth remains one of Mother Nature’s best kept secrets. By and large, doctors simply can’t explain why an otherwise healthy woman might go into labor early, making it difficult to treat patients with preventive measures, but as Mr. Churchill said, perhaps there is a key.

Though researchers struggle to uncover the exact causes of preterm birth, what studies have revealed are factors that are associated with prematurity. About 75 percent of preterm births are considered “spontaneous”— meaning there a known cause. The other 25 percent of preterm births are medically indicated. This happens when the mother has a condition such as Preeclampsia or the fetus is in distress, requiring preterm delivery to safe its life. Because the majority of preterm births are spontaneous, and therefore may be preventable, researchers have spent a great deal of time trying to understand what makes a women go into labor early. But, in some cases, it seems the more researchers work to unravel the mystery, the more they realize just how complex the issue is. Years of research has shown that preterm birth is likely the result of a complex interaction of biological, behavioral, social, physical and environmental factors.

“We’ve learned a lot over the years about what might cause preterm birth, and certain factors that put women at risk, but we’ve also learned a lot about what doesn’t work in predicting or preventing it,” said Michal Elovitz, MD, a professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, director of the Maternal & Child Health Research Center at Penn and director of Penn’s Prematurity Prevention Program. “Conventional wisdom once held that preterm birth was a result of something happening in the uterus. For years, we were focused on what was going on in the uterus, but it wasn’t getting us anywhere. Those traditional approaches — trying to stop contractions in the uterus — just were not working, so we had to start thinking outside of the box. Every time we realize that something isn’t working, it’s an indicator that we’re missing something and we need to think beyond what we already believed about how preterm birth occurs.”

Credit: National Institutes of Health

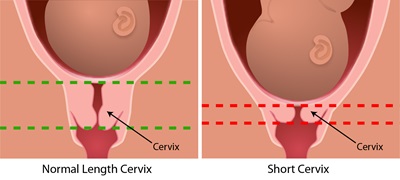

Elovitz, whose work focuses specifically on how biological, molecular and microbial changes in the cervix and vagina might lead to preterm birth, was part of a research team that

recently published a study showing that a common method of screening for preterm birth risk actually only identified only a small proportion of all cases. In order for labor to occur and the fetus to be delivered, the cervix must shorten and open. Previous research suggesting a short cervix early in pregnancy could be a warning sign of preterm birth has made sonographic cervical-length measurement a routine part of obstetrical care.

“It’s disappointing because these results suggest that this screening method is not sufficient to identify the majority of women at risk for preterm birth,” said Elovitz. “ However, Elovitz notes that she is not entirely surprised by the results. “Our research suggests that we understand very little about the cervix and its function during pregnancy, term labor and preterm labor. Shortening of the cervix, as noted by ultrasound assessment, is a limited metric. It’s likely that the cervix can change molecularly and be on a path to ‘opening’ and the length might not change till labor is already active.” Elovitz says the results indicate a need for better screening tests, but researchers must first understand the mechanisms behind preterm birth.”

Also contrary to previous research, the study showed that testing for fetal fibronectin, a glue-like protein that secures the amniotic sac to the inside of the uterus, is not an accurate predictor of preterm birth.

As part of Penn’s March of Dimes Prematurity Research Center, Elovitz and a team of researchers from vast and varied disciplines, work to specifically understand how the cervix changes during pregnancy (known as cervical remodeling), and whether something in that process goes awry in women who have a preterm birth. The team, which includes experts in bioengineering, immunology and microbiology, is working to understand the processes that control changes in the cervix during preterm birth. One possibility they are exploring, is the role that bacteria in the cervix and vagina might play in triggering preterm birth.

Early studies from Elovitz’s research showed that the cervical vaginal microbiome - a community of bacteria that normally inhabit the body - may be different in women who go on to have a preterm birth.

“We suspect that in some women, the cervicovaginal microbiome shifts, and that this shift, or a loss of ‘good’ bacteria or a gain of ‘bad’ bacteria leads to disruption of the epithelial barrier, which protects the cervix,” Elovitz says. “We don’t know what causes the shift, or who is at risk – it could be caused by lifestyle choices, like smoking or diet, it could be genetic, or it could based on the woman’s local immune response – but it seems these bacteria are a big missing piece of the puzzle.”

Recently published research from the team suggests they are on the right track. In a study presented earlier this year, results showed that bacteria found in the cervical and vaginal microbiomes are significantly linked to the risk of premature birth. That study was the first in years to make substantial strides toward understanding the causes of preterm birth, and even went so far as to identify specific species of bacteria that increase or decrease risk. Higher levels of bifidobacterium and lactobacillus, for example, were shown to lower risk of premature birth, while higher levels of certain anaerobic bacteria were linked to a higher risk.

"Decoding the causes of prematurity has been a riddle that's stumped researchers and clinicians for years,” she told MedPage Today. “But … we are finally shedding some light on a path toward offering treatment to women we can identify as being at-risk. Whether we’re realizing that screening tests and treatments aren’t working, or uncovering a new direction of study, it’s all good. It’s progress.”