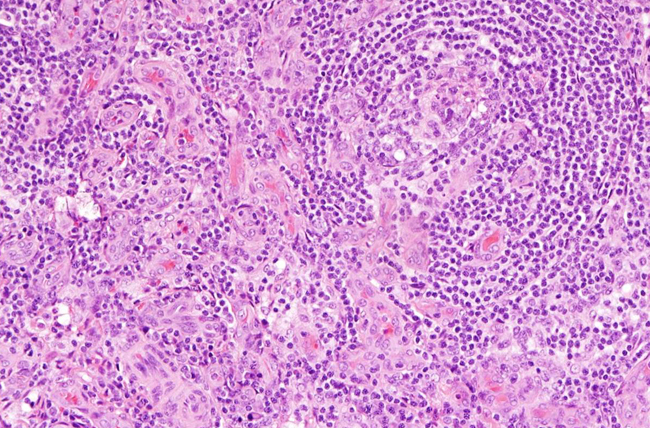

Example of lymph node tissue from a person with idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Image shows Increased number of blood vessels and smaller germinal centers where immune cells mature in the lymph node, which are two of the pathology features needed to make the diagnosis.

Credit: David Fajgenbaum, MD, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

PHILADELPHIA – More than six decades after Castleman disease (CD) was first described, a group of experts from

Penn Medicine and other institutions around the world has established the first set of diagnostic criteria for a life-threatening subtype of the condition, idiopathic multicentric CD (iMCD), which is often misdiagnosed as other illnesses. The report was

published online ahead of print in the journal

Blood.

Accurate diagnosis of iMCD has been challenging, with no standard diagnostic criteria to guide physicians and significant overlap with cancer and autoimmune, or infectious disorders. About 1,200 patients are diagnosed with iMCD each year in the United States. It can occur in patients of any age, and about 35 percent of iMCD patients die within five years of diagnosis; 60 percent die within 10 years.

“The new criteria will accelerate time to diagnosis and, more importantly, administration of life-saving treatments for iMCD patients," said first author David Fajgenbaum, MD, MBA, MSc, an assistant professor of Medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and associate director of patient impact at the Penn Orphan Disease Center.

Many iMCD patients endure months without appropriate treatment, including Fajgenbaum, who is also an iMCD patient. It took over 11 weeks for Fajgenbaum to be correctly diagnosed, during which time he experienced two life-threatening episodes of the disease.

“Previously, patients had to hope their doctors were familiar with the Castleman disease medical literature in order for them to even consider an iMCD diagnosis,” Fajgenbaum said. “Then, for the doctors considering the diagnosis, actually diagnosing it was very difficult. Now, with these criteria, doctors will know exactly what to look for and what to check off to feel confident about a diagnosis.”

To establish the criteria, the international working group – led by Fajgenbaum and consisting of 34 pediatric and adult hematopathology, hematology/oncology, rheumatology, immunology, and infectious diseases experts in iMCD and related disorders representing eight countries on five continents, including two physicians that are also iMCD patients – reviewed 244 iMCD cases and 88 lymph node tissue biopsies over 15 months.

Other working group members from Penn include senior authors Kojo Elenitoba-Johnson, MD, a professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and director of the Center for Personalized Diagnostics, and Megan Lim, MD, PhD, a professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine.

The criteria require that for a diagnosis of iMCD to be made, two major criteria and at least two of 11 minor criteria be met, including at least one laboratory abnormality, such as anemia or elevated C-reactive protein in the blood. Additionally, several diseases with similar clinical presentation to iMCD must be excluded, such as another sub-type of CD called HHV-8-associated multicentric CD.

Several therapies have been used off-label to treat iMCD patients with varying success, including corticosteroids, cytotoxic chemotherapy, and immunosuppressants. In 2014, siltuximab, an anti-IL6 monoclonal antibody used to treat cancer, became the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved iMCD therapy based on results from an international, randomized controlled trial in which 34 percent of patients had a complete or partial response to the drug compared to zero percent on placebo.

“However, the lack of a defined diagnostic criteria has likely impeded the timely administration of treatment for many patients,” Fajgenbaum said. “Such delays could lead to organ dysfunction and even death.”

The working group retrospectively applied the diagnostic criteria to patients from the siltuximab clinical trial. They found that individuals presumed to have iMCD, but who did not meet the diagnostic criteria, had a significantly lower (0 percent) response rate to siltuximab compared to patients who met the diagnostic criteria (43 percent).

The working group will continue to improve upon the new diagnostic criteria, in part by relying on the ACCELERATE patient registry. ACCELERATE is a CD natural history registry based at Penn. The data collected from the registry will help researchers validate and potentially tweak the criteria.

“I feel so pleased and optimistic that we're finally turning the tide against this disease,” Fajgenbaum said. “I've heard of too many patients diagnosed with the disease only after they died and underwent an autopsy, and hopefully this will help doctors to diagnose it before it is too late.”

Co-authors also include Elaine Jaffe, MD and Thomas S. Uldrick, MD, MS, from the National Cancer Institute’s Center for Cancer Research.

The study was supported in part by the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network, the Penn Orphan Disease Center, and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health.

Penn Medicine is one of the world’s leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, excellence in patient care, and community service. The organization consists of the University of Pennsylvania Health System and Penn’s Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine, founded in 1765 as the nation’s first medical school.

The Perelman School of Medicine is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $550 million awarded in the 2022 fiscal year. Home to a proud history of “firsts” in medicine, Penn Medicine teams have pioneered discoveries and innovations that have shaped modern medicine, including recent breakthroughs such as CAR T cell therapy for cancer and the mRNA technology used in COVID-19 vaccines.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System’s patient care facilities stretch from the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania to the New Jersey shore. These include the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Chester County Hospital, Lancaster General Health, Penn Medicine Princeton Health, and Pennsylvania Hospital—the nation’s first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional facilities and enterprises include Good Shepherd Penn Partners, Penn Medicine at Home, Lancaster Behavioral Health Hospital, and Princeton House Behavioral Health, among others.

Penn Medicine is an $11.1 billion enterprise powered by more than 49,000 talented faculty and staff.