PHILADELPHIA – By injecting human Alzheimer’s disease brain extracts of pathological tau protein (from postmortem donated tissue) into mice with different amounts of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques in their brains, researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania found that amyloid-β facilitates the interaction between the plaques and abnormal tau. This relationship promotes the spread of mutated tau proteins in neurons, which is the hallmark of long-term Alzheimer’s disease. They published their findings this week in Nature Medicine.

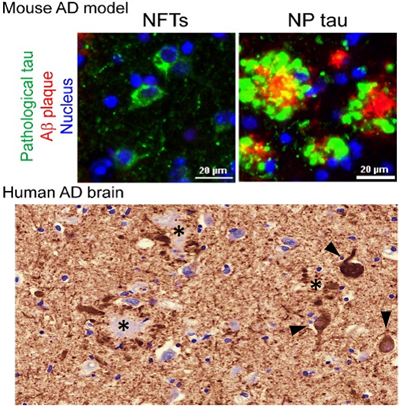

Upper panel: Tau clumps in new AD mouse model, either in the cell body as neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) or in dystrophic axons surround A-beta plaques as neuritic plaque tau (NP tau). Lower panel: tau clumps in human AD brain, as NFTs (arrow head) and NP tau.

Credit: The lab of Virginia Lee, PhD, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

“Making an AD mouse model that incorporates both Aβ and tau pathologies in a more AD-relevant context has been greatly sought after but difficult to accomplish,” said senior author Virginia M-Y Lee, PhD, director of the Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research (CNDR) at Penn. “This study is a big step for AD research, which will allow us to test new therapies in a more realistic context.”

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by Aβ plaques outside cells and clumps of tau within cells. Researchers have proposed that Aβ plaques are the initiating pathology of AD, but the failure of all AD clinical trials based on removing Aβ challenges this hypothesis and the idea of targeting Aβ alone to treat AD. At the same time, evidence from other studies, including research from CNDR, strongly correlates the spread of tau clumps with worsening cognition in AD, but the exact link between the two pathologies has remained enigmatic.

Tau works like railroad track crossties in stabilizing microtubules in axons responsible for transporting material inside neurons. Removal of tau protein from microtubules due to its clumping in nerve cells causes the affected neurons to become dysfunctional, ultimately leading to their death and AD.

The Penn team mimicked the formation of three major types of AD-relevant tau pathology in their new mouse model: neurofibrillary tangles, neuropil threads, and tau aggregates surrounding Aβ plaques, called neuritic plaque tau. “For the first time we could see and study the tau clumps in dystrophic axons surrounding Aβ plaques in a mouse model, just like we see in a human brain with AD,” said first author Zhuohao He, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Lee’s lab.

The team found that Aβ plaques create an environment that facilitates the rapid amplification and spread of pathological tau into large aggregates, initially appearing as neuritic plaque tau. This was followed by the formation and spread of neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads to other neurons. These tau protein formations also impaired brain functions, including memory difficulties, in the mice.

This study is the basis for a new way to explain how the Aβ plaque environment accelerates the spread of tau pathology in the brains of AD patients, which is consistent with imaging studies and investigations of postmortem AD brains.

The findings suggest new targets and strategies to treat AD patients. “Our new mouse model of AD with both Aβ and tau can now be used to test therapies that target one or both pathologies to see if combination or single-target therapy is better,” Lee said.

Study coauthors are Jing L. Guo, Jennifer D. McBride, Sneha Narasimhan, Hyesung Kim, Lakshmi Changolkar, Bin Zhang, Ronald J. Gathagan, Cuiyong Yue, Christopher Dengler, Anna Stieber, Magdalena Nitla, Douglas A. Coulter, Ted Abel, Kurt R. Brunden, and John Q. Trojanowski.

This study was funded by the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health (P30AG10124, P01AG17586, P01AG017628)

Penn Medicine is one of the world’s leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, excellence in patient care, and community service. The organization consists of the University of Pennsylvania Health System and Penn’s Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine, founded in 1765 as the nation’s first medical school.

The Perelman School of Medicine is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $550 million awarded in the 2022 fiscal year. Home to a proud history of “firsts” in medicine, Penn Medicine teams have pioneered discoveries and innovations that have shaped modern medicine, including recent breakthroughs such as CAR T cell therapy for cancer and the mRNA technology used in COVID-19 vaccines.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System’s patient care facilities stretch from the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania to the New Jersey shore. These include the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Chester County Hospital, Lancaster General Health, Penn Medicine Princeton Health, and Pennsylvania Hospital—the nation’s first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional facilities and enterprises include Good Shepherd Penn Partners, Penn Medicine at Home, Lancaster Behavioral Health Hospital, and Princeton House Behavioral Health, among others.

Penn Medicine is an $11.1 billion enterprise powered by more than 49,000 talented faculty and staff.