| > |

Researchers at the University

of Pennsylvania School of Medicine have found an

absolute biochemical distinction between the sporadic and

hereditary variants of Lou Gehrig’s disease, or

amyothrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), suggesting

that current approaches to drug discovery should be re-examined. |

| > |

By examining the various forms of ALS

in post-mortem tissue, the researchers found that TDP-43

was the disease protein in sporadic ALS cases, but not in

patients with SOD-1 mutations, all of whom have the familial

form of ALS. Patients with the SOD-1 mutation account for

about 1 percent of all ALS cases. |

| > |

This finding may partially account for

why therapeutic strategies, shown to be effective in SOD-1

mouse models, have generally not been effective in clinical

trials of sporadic ALS patients. |

| > |

The study was published this week in

the Annals of Neurology. |

(PHILADELPHIA) – Most research on Lou

Gehrig’s disease therapeutics has been based on the assumption that its two forms

(sporadic and hereditary) are similar in their underlying cause.

Now, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania

School of Medicine have found an absolute biochemical distinction between these two

disease variants, suggesting that current approaches to drug discovery

should be re-examined.

|

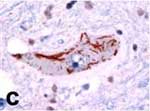

TDP-43 disease protein in amyotrophic

lateral sclerosis (ALS) brain tissue

Click on thumbnail

to view full-size image |

About 5 percent of all cases of Lou Gehrig’s disease, or

amyothrophic

lateral sclerosis (ALS), are passed from generation

to generation. The most common genetic variant in this familial

form is caused by a mutation in the SOD-1 gene. The researchers

looked at a large set of ALS patients, including hereditary cases,

both with and without the SOD-1 mutation.

The present study – published this week in the Annals

of Neurology – was conducted by Penn; a group led by Ian

Mackenzie from the University of British Columbia; the University

of Munich;

and others across the U.S. and Canada.

“Most ALS research has focused on how mutant SOD-1 proteins are toxic to nerve cells,” says senior author John

Trojanowski, MD, PhD, who directs the Penn Institute

on Aging. Last year, Penn

investigators led by co-author Virginia Lee,

PhD, who directs the

Penn Center for Neurodegenerative

Disease Research, identified

TDP-43 as the major disease protein in sporadic (non-hereditary)

forms of ALS, which are not those caused by SOD-1 gene mutations.

By examining the various forms of ALS in post-mortem tissue, the

researchers found that TDP-43 was the disease protein in sporadic

ALS cases, but not in patients with SOD-1 mutations, all of whom

have the familial form of ALS. Patients with the SOD-1 mutation

account for about 1 percent of all ALS cases.

“We argue that SOD-1 ALS does not equal sporadic ALS,” says

Trojanowski. “If you pursue drug discovery focusing on SOD-1-mediated pathways of brain and spinal cord degeneration you may benefit

SOD-1-bearing patients, but not the vast majority of ALS patients

who have the sporadic form of this disorder with TDP-43 pathologies underlying the disease.”

“Motor

neuron degeneration in TDP-43 cases may result from

a different mechanism than cases with SOD-1 mutations, so this

form of ALS may not be the familial counterpart of sporadic ALS,” surmises

Lee.

“This may also partially account for why therapeutic strategies,

shown to be effective in SOD-1 mouse models, have generally not

been effective in clinical trials of sporadic ALS patients,” explains

Trojanowski. “This also sounds a cautionary note in all other

diseases in which you have familial and sporadic versions of the

disease because it will prompt researchers to ask if mouse models

for drug discovery are based on the correct mutations or disease

protein.”

This research was funded by the Canadian

Institutes of Health Research, the National

Institute on Aging, the German

Federal Ministry of Education and Research, The

Wellcome Trust (United Kingdom) and the UK

Medical Research Council.

Co-authors in addition to Trojanowski, Lee, and Mackenzie are

Eileen H. Bigio, Paul G. Ince, Felix Geser, Manuela Neumann, Nigel

J. Cairns, Linda K. Kwong, Mark S. Forman, John Ravits, Heather

Stewart, Andrew Eisen, Leo McClusky, Hans A. Kretzschmar, Camelia

M. Monoranu, J. Robin Highley, Janine Kirby, Teepu Siddique, and

Pamela J. Shaw.

###

PENN Medicine is a $2.9 billion enterprise

dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical

research, and high-quality patient care. PENN Medicine consists

of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (founded in

1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of

Pennsylvania Health System.

Penn's School of Medicine is ranked #2 in the nation for receipt

of NIH research funds; and ranked #3 in the nation in U.S. News

& World Report's most recent ranking of top research-oriented

medical schools. Supporting 1,400 fulltime faculty and 700 students,

the School of Medicine is recognized worldwide for its superior

education and training of the next generation of physician-scientists

and leaders of academic medicine.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System includes three hospitals,

all of which have received numerous national patient-care honors [Hospital

of the University of Pennsylvania; Pennsylvania Hospital, the nation's

first hospital; and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center]; a faculty practice

plan; a primary-care provider network; two multispecialty satellite

facilities; and home care and hospice.

Penn Medicine is one of the world’s leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, excellence in patient care, and community service. The organization consists of the University of Pennsylvania Health System and Penn’s Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine, founded in 1765 as the nation’s first medical school.

The Perelman School of Medicine is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $550 million awarded in the 2022 fiscal year. Home to a proud history of “firsts” in medicine, Penn Medicine teams have pioneered discoveries and innovations that have shaped modern medicine, including recent breakthroughs such as CAR T cell therapy for cancer and the mRNA technology used in COVID-19 vaccines.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System’s patient care facilities stretch from the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania to the New Jersey shore. These include the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Chester County Hospital, Lancaster General Health, Penn Medicine Princeton Health, and Pennsylvania Hospital—the nation’s first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional facilities and enterprises include Good Shepherd Penn Partners, Penn Medicine at Home, Lancaster Behavioral Health Hospital, and Princeton House Behavioral Health, among others.

Penn Medicine is an $11.1 billion enterprise powered by more than 49,000 talented faculty and staff.